The pagoda in Japan is called tō (塔 lett. pagoda), sometimes buttō (仏塔 lett. Buddhist pagoda) or tōba (塔婆 lett. pagoda) and is historically derived from the Chinese pagoda, itself an interpretation of the Indian stupa. Like the stupa, pagodas were originally used as reliquaries but in many cases ended up losing this function.

Pagodas are a quintessential part of Buddhism and an important component in Japanese Buddhist temple complexes, but since until the Kami-Buddha separation law of 1868, a Shinto shrine was normally also a Buddhist temple and vice versa, they are not uncommon in shrines either.

The famous Itsukushima Shrine, for example, has one.

After the Meiji Restoration, the word tō, once used exclusively in a religious context, also meant "tower" in the Western sense, such as for the Eiffel tower (エッフェル塔 Efferu-tō).

Of the many forms of the Japanese pagoda, some are built of wood and are known collectively as mokutō (木塔 lit. wooden pagoda), but most are carved in stone (sekitō (石塔 lit. stone pagoda). Wooden pagodas are large buildings with two stories (such as tahōtō (多宝塔 lit. Tahō pagoda) or an odd number of stories.

Existing wooden pagodas with more than two floors almost always have three (and are therefore called sanjū-no-tō (三重塔 lett. three-story pagoda) or five (and are called gojū-no-tō (五重塔 lett. five-story pagoda).

Stone pagodas are almost always small, usually well under 10 feet, and usually offer no usable space. If they have more than one floor, they are called tasōtō (多層塔 lett. multi-story pagoda) or tajūtō (多重塔 lett. multi-story pagoda).

The size of a pagoda is measured in ken, where a ken is the interval between two pillars of a traditional style building. A tahōtō for example may be 5x5 ken or 3x3 ken.The word is usually translated into English as "bay" and is better understood as an indication of proportions than as a unit of measurement.

Japanese Pagoda History

The stupa was originally a simple mound containing the ashes of the Buddha, which over time became more elaborate as its pinnacle grew proportionately larger. After reaching China, the stupa met the Chinese watchtower and developed into the pagoda, a tower with an odd number of floors.

Its use then spread to Korea and from there to Japan. Following its arrival in Japan along with Buddhism in the sixth century, the pagoda became one of the focal points of the early Japanese garan.

In Japan it evolved in shape, size, and functionality, eventually losing its original role as a reliquary. It also became extremely common, while on the Asian continent it is rare.

As new sects emerged in later centuries, the pagoda lost importance and was consequently relegated to the fringes of the garan. Temples of Jōdo sects rarely have a pagoda. During the Kamakura period, the Zen sect arrived in Japan and their temples normally do not include a pagoda.

Pagodas were originally relics and did not contain sacred images, but in Japan many, for example the five-story pagoda at Hōryū-ji, hold statues of various deities.

To allow a room to be opened up on the ground floor and thus create a usable space, the central rod of the pagoda, which originally touched the ground, was shortened on the upper floors, where it rested on support beams.

Statues of the temple's main objects of worship are kept in that room. Inside the Shingon pagodas there may be paintings of deities called Shingon Hasso (真言八祖); on the ceiling and central body there may be decorations and paintings.

Japanese Pagoda Style and evolution of the structure

The eave edge of a pagoda forms a straight line, with each successive edge shorter than the other. The greater the difference in length (a parameter called teigen (逓減 gradual decrease) in Japanese) between the planes, the more solid and secure the pagoda seems to be.

Both the teigen and fastigium are greater in older pagodas, giving them a sense of solidity. Conversely, recent pagodas tend to be steeper and have shorter pinnacles, creating thinner silhouettes.

Structurally, older pagodas had a stone base (心礎 shinso) beyond which stood the main pillar (心柱 shinbashira). Around it would be erected the pillars supporting the second floor, then the beams supporting the eaves, and so on.

The other floors would be built on top of the completed one, and at the top of the main pillar the fastigium would finally be inserted. In later eras, all the supporting structures would be erected at once, and later parts with a more aesthetic function were attached to them.

Early pagodas had a central pillar that penetrated deeply into the ground. As architectural techniques evolved, it was first set at rest on a stone base at ground level, then shortened and set at rest on beams on the second floor to allow for the opening of a room.

Their role within the temple gradually diminished as they were functionally replaced by the main halls (kondō). Originally the focus of the Shingon and Tendai garan, they were later moved to its edges and eventually abandoned, particularly by the Zen sects, the last to appear in Japan.

Loss of importance of the pagoda within the garan.

Because of the relics they contained, the wooden pagodas were the centerpiece of the garan, the seven buildings considered essential to a temple. They gradually lost importance and were replaced by the kondō (golden hall), due to the magical powers falsely believed to be found within the images housed in the building.

This loss of status was so complete that Zen schools, which arrived late in Japan from China, normally have no pagoda in their garan. The layout of the four temples clearly illustrates this trend: they are in chronological order Asuka-dera, Shitennō-ji, Hōryū-ji, and Yakushi-ji.

In the first, the pagoda was in the center of the garan surrounded by three small kondō. In the second, a single kondō is in the center of the temple and the pagoda is in front of it. In the Hōryū-ji, they are next to each other. The Yakushi-ji has a single, large kondō in the center with two pagodas on either side. The same evolution can be seen in Buddhist temples in China.

The stone pagodas

Stone pagodas (sekitō) are usually made of materials such as apatite or granite, are much smaller than wooden ones, and are finely carved. They often bear Sanskrit inscriptions, Buddhist figurines, and dates from the Japanese nengō lunar calendar.

Like those made of wood, they are mostly classifiable on the basis of the number of stories as tasōtō or hōtō, but there are, however, some styles almost never seen in wood, namely gorintō, muhōtō, hōkyōintō, and kasatōba.

Tasōtō or tajūtō

With some very rare exceptions, tasōtō (also called tajūtō, 多層塔) have an odd number of stories, normally between three and thirteen. They are usually less than three meters high, but can sometimes be much taller. The tallest still in existence is a 13-story pagoda at Hannya-ji in Nara, which is 14.12 m (14 ft).

They are often dedicated to the Buddha and offer no usable space, but some have a small space inside which a sacred image is kept. In the oldest extant example, while the edge of each floor is parallel to the ground, each successive floor is smaller, resulting in a steeply sloping shape. More modern tasōtō tend to have a less pronounced shape.

Hōtō

A hōtō (宝塔 lit. jeweled stupa) is a pagoda consisting of four parts: a low foundation stone, a cylindrical body with a rounded top, a four-sided roof, and a pinnacle. Unlike the tahōtō which is similar it does not have a pitched roof (mokoshi) around its circular core.

Like the tahōtō it is named after the Buddhist deity Tahō Nyorai. Hōtō arose during the early Heian period, when the Tendai and Shingon sects first arrived in Japan. In fact, because it does not exist on the Asian continent, it is believed to have been invented in Japan.

There was a life-size hōtō, but almost only miniature ones survive, normally made of stone and/or metal.

Gorintō

The gorintō (五輪塔 lett. five-ringed tower) is a pagoda found almost only in Japan and is believed to have been first adopted by the Shingon and Tendai sects during the mid-Heian period.

It is used as a tombstone or cenotaph, and is thus a common sight in Buddhist temples and cemeteries. It is also called gorinsotōba (五輪卒塔婆) ("five-ring stupa") or goringedatsu (五輪解脱), where the term sotoba is a transliteration of the Sanskrit word stupa. It is also called gorinsotōba.

In all of its variations, the gorintō consists of five blocks (although sometimes this number can be difficult to detect), each with one of the five shapes symbolizing the Five Elements that are believed to be the fundamental building blocks of reality: earth (cube), water (sphere), fire (pyramid), air (crescent), and ether, energy, or vacuum (lotus).

The last two rings (air and ether) are visually and conceptually combined into one subgroup.

Hōkyōintō

The hōkyōintō (宝篋印塔) is a large stone pagoda so named because it originally contained the Hōkyōin (宝篋印) Dhāraṇī (陀羅尼) sūtra. It was originally used as a cenotaph for the king of Wuyue - Qian Liu in China.

It is believed that the tradition of the hōkyōintō in Japan began during the Asuka period (550-710). They were made of wood and only began to be built of stone during the Kamakura period. It is also during this period that they began to be used as tombstones and cenotaphs.

The hōkyōintō began to be built in its current form during the Kamakura period. Like a gorintō, it is divided into five main sections representing the five elements of Japanese cosmology.

The sūtra it sometimes conceals contains all of the pious works of a Tathāgata Buddha, and worshippers believe that by praying before the hōkyōintō, their sins will be erased, during their lifetime they will be protected from disasters, and after death they will go to heaven.

Muhōtō or rantō

The muhōtō (無縫塔 lett. no point tower) or rantō (卵塔 lett. egg tower) is a pagoda that usually marks the tomb of a Buddhist priest. Initially it was used only by Zen schools, but was later adopted by others. Its distinctive egg-shaped top is supposed to be a phallic symbol.

Kasatōba

A kasatōba (笠塔婆 umbrella stupa?) is simply a square stone pole placed on a square base and covered by a pyramidal roof. Above the roof is a bowl-shaped stone and a lotus-shaped stone. The pole may be carved with Sanskrit words or low relief images of Buddhist deities. Inside the pit there may be stone wheels that allow worshippers to spin around the stupa while praying as with a prayer wheel.

Sōrintō

The sōrintō (相輪橖) is a type of small pagoda consisting of only a pole and a sōrin.

Wooden pagoda

Tasōtō

Wooden tasōtō are pagodas with an odd number of floors. Some may appear to have an even number because of the presence between the floors of roofs designed purely for decorative purposes and called mokoshi.

A famous example is the eastern pagoda of Yakushi-ji, which appears to have six floors but actually has only three. Another is the tahōtō (see below), which has only one floor, plus a mokoshi under its roof, and thus appears to have two floors.

There were examples with seven or nine floors, but all existing ones have three (and are thus called) sanjū-no-tō (三重塔 lett. three-story pagoda) or five (and are called gojū-no-tō (五重塔 lett. five-story pagoda). (Tanzan Jinja in Sakurai, Nara, has a pagoda with thirteen stories, which, however, for structural reasons is classified separately, and is not considered a tasōtō.)

The oldest three-story pagoda is located at Hokki-ji in Nara and was built between 685 and 706. The oldest extant five-story pagoda belongs to Hōryū-ji and was built during the Asuka period (538 -710). The tallest wooden tasōtō belongs to Tō-ji, Kyoto. It has five stories and is 54 m high.

Hōtō

A wooden hōtō is a rare type of pagoda consisting of four parts: a low foundation stone, a cylindrical body with a rounded top, a pyramidal roof, and a pediment. Unlike the tahōtō which is similar (see section below) it does not have a closed square roof (mokoshi) around its cylindrical core.

Like the tahōtō it is named after the Buddhist deity Tahō Nyora. The hōtō arose during the early Heian period, when the Tendai and Shingon Buddhist sects first arrived in Japan.

There were many life-size hōtō, but almost only miniature ones survive, normally made of stone and/or metal. A good example of a life-size hōtō can be seen at the Ikegami Honmon-ji in Nishi-magome, Tokyo. The pagoda is 17.4 meters high and 5.7 meters wide.

Tahōtō

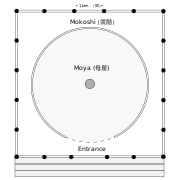

The tahōtō is a type of wooden pagoda unique for having an even number of floors (two), the first surface with a rounded core, the second circular. This style of tō was created by surrounding the cylindrical base of a hōtō (see above) with a covered square corridor called a mokoshi.

The core of the pagoda has only one floor with its ceiling below the second circular floor, which is inaccessible. Like the tasōtō and rōmon, despite its appearance, it therefore only offers usable space on the ground floor.

Since this genre does not exist in either Korea or China, it is believed to have been invented in Japan during the Heian period (794 - 1185). The tahōtō was important enough to be considered one of the seven indispensable buildings (the so-called shichidō garan) of a Shingon temple. Kūkai himself is responsible for the construction of the tahōto in the Kongōbu-ji of Mount Kōya.

Daitō

Usually the base of a tahōtō is 3-ken with four main supporting pillars called shitenbashira (四天柱) on either side (see drawing). The room in the shape of the shitenbashira houses a shrine where the main objects of worship (the gohonzon) are kept.

The largest 5x5 ken tahōtō however exist and are called daitō (大塔 lett. pagoda grande) because of their size. This is the only type of tahōtō that retains the original structure with a wall separating the corridor (mokoshi) from the core itself.

This type of pagoda was common, but of all the daitō ever built, only three are still standing. One is at Negoro-ji in Wakayama Prefecture, another at Kongōbu-ji, again in Wakayama, and the last at Kirihata-dera, Tokushima Prefecture. The daitō at Kongōbu-ji was founded by Kūkai of the Shingon sect. The specimen found at Negoro-ji is 30.85 meters high and is a national treasure.

Sotōba

Often wooden offering strips with five subdivisions covered with elaborate inscriptions called sotōba (卒塔婆) can be found in graves in Japanese cemeteries. The inscriptions contain sūtra and the posthumous name of the person who died. Their name is derived from the Sanskrit stupa, and they can also be considered pagodas.